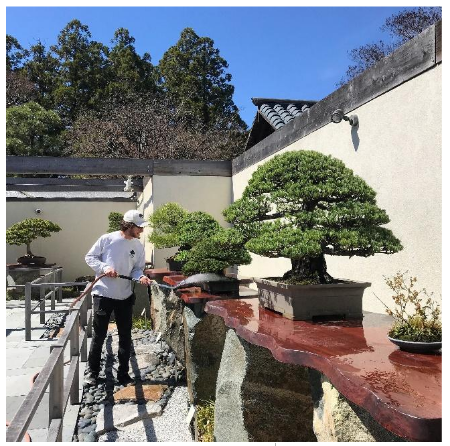

Japanese white pine donated by Masaru Yamaki, in training since 1625. This photo was taken on August 6, 2020 to commemorate its survival of the atomic bombing in Hiroshima, Japan 75 years ago. Photos courtesy of U.S. National Arboretum.

In early spring, as COVID-19 cases increased, many businesses and public places implemented restrictions or completely shuttered their doors. As many of you know, this was the fate of the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum. We had to close to ensure the safety of our visitors, volunteers, and staff. It has been about six months since the closure, but within the walls of the Museum we have been hard at work building the strength of the trees and continuing to bring the intended designs forward.

One positive aspect of closing to the public is that the trees had an opportunity to grow out of their constantly maintained forms and build more strength and vigor. By letting new growth elongate and allowing the leaves mature, the trees were able to photosynthesize to a greater extent and recover the energy they used to push growth in spring. What might look like a slightly overgrown small shrub in a beautiful container is just a bonsai gaining energy and being pampered until it is once again brought back into shape for the viewer to gaze upon and enjoy.

Bonsai in the Japanese Collection soaking up the summer sun after a morning watering.

Bonsai in the Japanese Collection soaking up the summer sun after a morning watering.

As spring slowly passed and we began to settle into summer here in D.C., we experienced an intense heat wave. At this point in the year most of the trees have been repotted and their spring growth has been pruned. As the heat increases, the focus turns to attentive watering. Watering, as many people who practice bonsai know, is the first thing you learn and the last thing you master. Local weather conditions can vary greatly, especially in the temperate areas of the continental United States. With this weather variability, we must also change how we water. We can’t let trees get too dry or keep them too wet, causing rot and encouraging the onset of diseases or pests. Watering is a delicate process that gives me the greatest personal connection with each tree.

Closing the Museum to the public has also meant it is closed to our wonderful team of volunteers. Although we have been able to keep up with most of the work with our small staff, the skills, knowledge, and friendship that the volunteers provide to the Museum have been greatly missed.

As we approach summer’s end, we are looking forward to when we can once again open the gates of the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum and welcome our visitors and supporters to a safe space to enjoy the beauty, peace, and joy that bonsai provides to us all.

Sincerely,

Andy Bello

Assistant Curator

National Bonsai & Penjing Museum

U.S. National Arboretum