Walking through the Museum, you’ll find plaques with titles, donor names and dates next to most of the bonsai. But do you know how to tell which style our trees are exhibiting?

To help you wow friends on your next visit, Museum curator Michael James walked us through the main styles of bonsai on display in our pavilions: cascade, upright, root-over-rock, forest and windswept. James said these configurations simplify and categorize trees’ common forms or growth habits after enduring forces of nature – like wind, ice and snow – that shape trees in the wild.

“These are just styles that mimic what’s found happening in trees growing in harsh conditions,” he said.

The formal upright style is a simple design: the tree’s apex stands directly over the base of the trunk, and the tree is perfectly straight. James said the informal upright design is a bit looser and more whimsical than formal upright. The tree’s apex remains in line with the base of the tree, but the trunk twists and turns on its way to the top.

An informal upright bonsai.

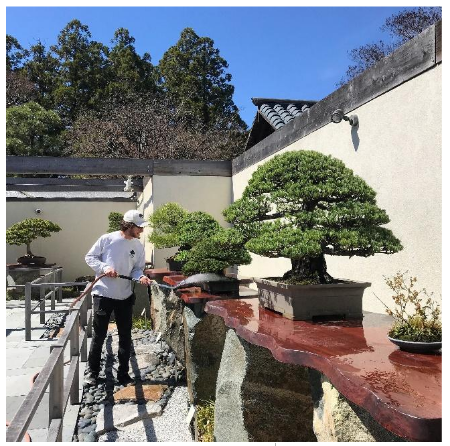

Forest style displays are created to mirror the different heights and trunk thicknesses found in natural forests, so the trees should differ randomly in size, James said. He added that the displays are usually arranged in odd numbers, ranging from about five to 11 trees.

A forest bonsai display.

Seeds that land on a small patch of fertile soil germinate and send roots down into the earth to create a tree. But over the years that bit of soil can erode, exposing the rock underneath where the tree began to grow. This process creates the root-over-rock look.

A root-over-rock style bonsai.

To replicate this style, bonsai masters will plant a bonsai on top of a rock. In some plantings, the masters attach the bonsai to the rock with wires and the tree lives entirely on the rock, growing in a special soil mix.

In other cases, as the above picture demonstrates, the rock and attached tree are planted in a container filled with soil, and the bonsai roots grow into the soil. In this instance, each time the bonsai is repotted, the master may lift the rock and attached tree higher in the container and remove some of the soil, exposing more of the roots and the rock.

A full-cascade bonsai.

Bonsai in the cascade style also come in two configurations. In the semi-cascade design, the trunk of the tree might lean over and drop below the lip of its pot. But the tip of bonsai in full-cascade reaches below its container, to emulate a tree clinging to a cliffside.

A bonsai in the windswept style.

The Museum has one tree that displays the windswept look: the iconic Chinese elm. Branches of windswept bonsai grow in one direction and look as if the tree is growing while enduring a strong wind blowing from only one side.

James said some styles are more common in certain trees, but many trees can be trained into myriad configurations. One exception is with cascade bonsai. Trees in the cascade category are often flowering trees or conifers, like pines and junipers, which are found in mountainous areas. Their low hanging branches are pulled down by the weight of fruit or snow and ice that accompany high-altitude conditions, creating the cascade look.

He added that some styles fit specific occasions, as certain designs are more formal than others.

“If you were displaying a bonsai for a special occasion you would use a formal tree, which would be very stately, maybe austere – very proper,” James said. “But an informal tree lends itself more to having a party or a big celebration. Something fun, maybe even more playful.”

Looking to learn even more about bonsai, and get your hands-on experience while doing it? Join our Museum Staff and Volunteers as they offer several Intro to Bonsai classes this July. Learn more here.